Low-Cost Generic Ketamine Shows Long-Term Effectiveness for Depression

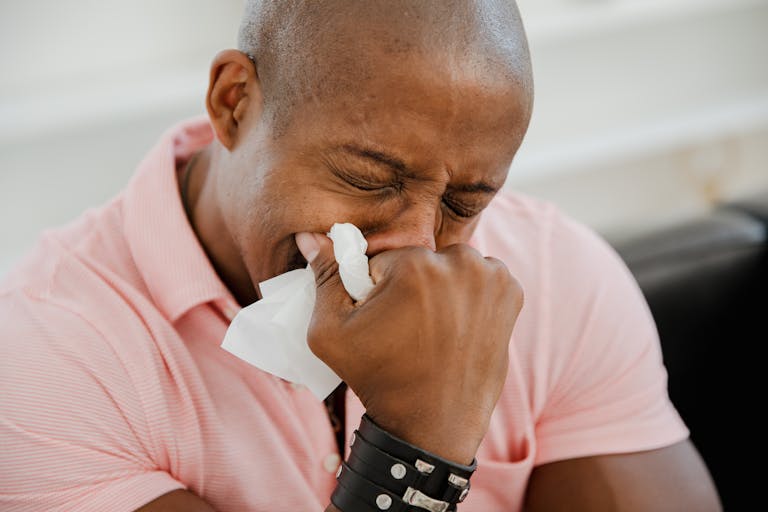

A new Australian study has found that generic ketamine, a low-cost formulation of the well-known anesthetic, is not only effective but also safe for long-term treatment of severe depression. The research, led by the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney) and the Black Dog Institute, provides strong real-world evidence that this affordable version of ketamine can offer lasting relief for people struggling with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—a form of depression that does not improve with standard antidepressants.

What the Study Found

Between 2021 and 2024, researchers followed 65 patients diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar Affective Disorder who had failed to respond to at least two antidepressant medications. These patients received generic racemic ketamine treatment across three clinics that are part of the CARE Network in Australia.

Treatment lasted an average of five months, with some patients continuing for up to six months. The drug was administered either by injection or taken orally, depending on patient preference and clinical judgment. The frequency of dosing ranged from twice a week to once every three weeks, tailored to each patient’s response and tolerance.

By the eighth week, about 35% of patients showed a clear improvement in depressive symptoms. By the six-month mark, 44.2% had responded positively, and 26.2% achieved full remission. Importantly, suicidal thoughts improved in 73.3% of participants, and many reported a better quality of life.

These results are significant because they show that the improvements seen in the first two months were largely sustained over time. For many individuals who have lived with unrelenting depression, that level of ongoing relief can be life-changing.

Safety and Tolerability

The study carefully monitored safety using a structured assessment called the Ketamine Side Effect Tool (KSET). This tool helps clinicians evaluate patients before, during, and after each treatment session to track possible side effects or safety issues.

The findings were encouraging: no serious side effects or misuse were reported throughout the study period. Most patients tolerated the treatment well, suggesting that when used responsibly and under medical supervision, generic ketamine can be a safe long-term option for TRD.

Of course, like any medical treatment, ketamine isn’t free from potential risks. Mild and short-term side effects such as dizziness, dissociation, or nausea can occur, but in this study, these were generally well managed by clinicians.

How the Research Was Conducted

This was a retrospective observational study, meaning researchers analyzed data from real-world clinical practice rather than running a controlled experiment. Because of this, there was no control group—no group of patients receiving placebo or alternative treatment to compare against.

That limits how confidently researchers can say the benefits were caused by ketamine alone. Some patients may have improved due to other ongoing treatments, like therapy or medication adjustments. Additionally, patients who stopped treatment before eight weeks were excluded from analysis, which might slightly bias results toward more positive outcomes.

Still, this kind of real-world study is valuable because it reflects how treatments actually work in practice, not just in tightly controlled lab conditions.

The Cost Divide: Generic Ketamine vs. Spravato

One of the most striking parts of this story is the cost difference between generic ketamine and its patented cousin, S-ketamine, marketed as Spravato.

- Generic racemic ketamine: Costs between $5 and $20 per dose.

- Spravato (S-ketamine nasal spray): Costs between $500 and $900 per dose.

The difference is enormous. However, Spravato is now approved by Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and subsidized through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), meaning patients only pay up to $31.60 per prescription.

In contrast, generic ketamine—despite showing strong results—remains off-label for depression. Because it doesn’t have a commercial sponsor, there’s no mechanism to fund the expensive regulatory approval process needed to make it eligible for government subsidy.

This has created an odd situation: the affordable option is less accessible than the expensive one, even though both seem to be effective for depression.

Why the Research Matters

This isn’t the first time ketamine has shown promise for depression. A previous UNSW trial called KADS (Ketamine for Adult Depression Study) found that short-term use of generic ketamine was safe and effective. However, most earlier studies only lasted a few weeks. This new research fills a key evidence gap by demonstrating that ketamine’s benefits can be maintained safely for up to six months.

The authors plan to go further, with a head-to-head clinical trial directly comparing generic racemic ketamine and S-ketamine. The goal is to understand whether there are meaningful differences in long-term effectiveness, safety, or tolerability between the two formulations.

They also intend to keep tracking real-world data over several years to learn more about how patients fare with ongoing ketamine therapy—how long the effects last, when relapses occur, and what dosing schedules work best.

Depression and Why Treatment-Resistant Cases Are So Challenging

Depression affects more than 280 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. For many, antidepressants and psychotherapy provide substantial relief. But around one-third of patients experience treatment-resistant depression (TRD), meaning they don’t respond adequately to at least two standard treatments.

People with TRD often face persistent low mood, loss of motivation, and suicidal thoughts even after trying multiple therapies. The condition is emotionally and economically devastating, often leading to lost work productivity and strained personal relationships.

Ketamine offers something unique because it works differently from traditional antidepressants. Instead of targeting serotonin or norepinephrine, ketamine acts on the glutamate system and helps form new neural connections in the brain. This may help “reset” brain activity patterns associated with depression.

Unlike conventional antidepressants that can take weeks to work, ketamine can produce improvements within hours or days—a major advantage for patients with severe or suicidal depression.

The Larger Issue: Access and Equity in Mental Health Treatments

Despite growing evidence that generic ketamine works, its lack of formal approval means patients must pay out of pocket, often hundreds of dollars per month. This has led to significant inequality in access—only those who can afford private clinics can receive it.

Experts have pointed out that this is part of a bigger systemic problem. The pharmaceutical system rewards innovation and patents but offers little incentive to fund clinical research on older, off-patent drugs. Without that research, regulatory agencies can’t formally approve them for new uses, even if real-world data supports their effectiveness.

If governments or public institutions don’t step in to fund such studies and approvals, effective low-cost treatments like generic ketamine may remain out of reach for many who need them most.

Looking Ahead

Researchers describe ketamine as one of the most important breakthroughs in depression treatment in the last 80 years. However, the challenge now lies not just in proving that it works—but in making it accessible.

This study adds to the growing momentum behind ketamine therapy and highlights the urgent need for policy reform, funding support, and structured clinical frameworks to bring affordable mental health treatments to everyone who needs them.

For now, the message is clear: low-cost generic ketamine is both effective and safe when used responsibly—and it may represent a turning point in how we approach treatment-resistant depression worldwide.

Research Reference:

Real-world clinical data on the long-term effectiveness and safety of generic racemic ketamine treatment – Journal of Affective Disorders (2026)